Classical performance practice in the ’30s

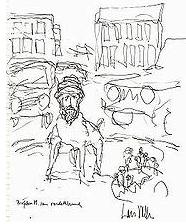

Drawing of Furtwangler by Lisl Steiner

Drawing of Furtwangler by Lisl Steiner

Notes from an eyewitness

Theses, monographs and books have been written about orchestral and instrumental performance practice in the Baroque, Classical, and even the Romantic eras. Indeed, the entire authentic performance and authentic instrument movement, the ‘period performance’ movement, is an attempt to recreate performances of the past. This movement exploded into academic and musical popularity in the ’60s and early ’70s, and resulted in a great deal of textual research and, on the whole, progress in the authentic recreation of historical instruments.

The recreation of performance practice, however, was disappointing. Thousands of recordings were made by ‘academically informed’ conductors and soloists. Too many were thin, metronomic, and dry as dust. After three decades a reaction set in. The younger generation pointed out that few historical documents existed on performance practice and those that did, including autograph scores, were usually ambiguous.

Recent research has turned to early recordings, on the theory that performance practice from the first decades of the last century must have reflected 19th century practice . . . which in turn might have included some survivals of 18th century practice. Unfortunately, electrical recording did not come in until 1926, and acoustical records from the previous three decades are dim and distorted. Nevertheless, the early electricals were examined. The latest scholarly opinion suggests that late 19th century and early 20th century performance practice was probably flexible in tempo and interpretatively free by modern standards.

But in an effort to find out exactly how something was generally played, say, during the classical period, might we be chasing a chimera? Isn’t it possible that there existed a wide variety of performance practice in every period?

Elizabeth Mittler-Laudy is 101 years old and living independently in Toronto. In the ’30s she was a professional violinist in Holland. In 1940 in Banyuls-sur-Mer, while in flight from the Nazis, she performed publicly with Wanda Landowska. I recently asked her to describe performance practice during that period, and particularly her experience performing with Landowska. Here is her reply:

Concerning (her) tempo there were slight variations within the flow of the music. It was just her deep feeling for the score that told her when to apply this and how much. At the time it seemed completely natural to me and I took it as just the way Bach should be

played.

In Holland I had played in a special Bach orchestra with a conductor who believed in a strict, almost metronomical beat, hardly slowing down at the last bars. To me it was very unsatisfying. I played a number of St Matthew Passions under different conductors and I found that the tempos and the general approach was a bit different with each one. It is difficult to point to a general accepted style used in the thirties. I believe that it mostly depended on the conductor or the soloist.

While thinking about Wanda Landowska it came to me that I once differed with her about the last bars in Bach’s Concerto for two Violins. She wanted them to be drawn out considerably. The word she used was “majestueusement”. I thought it was just a bit too

much, but who was I to question her judgment?

Landowska continued to perform for another 18 years on both the harpsichord and the piano. Her early recordings on the harpsichord can show great liberty in tempo and ornament; her late recording, below, of Haydn’s F Minor Variations, done in her own home in Lakeville, Connecticut, on her own Steinway, in 1957, shows by comparison a classical restraint. When playing Mozart and Haydn, she attempted to reproduce on the modern piano the sonority and dynamic range available to the fortepiano. I think she did a pretty good job.

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Note: this entry on performance practice was inspired by reading The Krupp Secret, a privately printed memoir by Elizabeth Mittler-Laudy.